Orion-Saturn Worship (2) Extract from Orion’s Door

In Australia they celebrate Easter the exact same way we do, commemorating the death and resurrection of Jesus by telling our children that a giant bunny rabbit left chocolate eggs in the night. Bill Hicks

Another important religious focus point is Easter, a time when children are often taught to connect Pagan origins with Judeo-Christian beliefs. A connection that uncomfortably tries to equate a giant rabbit, or ‘hare’, with the crucified star man, Orion. It’s a mad, ‘mad, world’, especially when ‘State and religion’ would have children focusing on the ritual killing of Jesus (the crucifixion), in one hand, while celebrating the return of a ‘giant bunny’ delivering chocolate eggs, with the other. Giant rabbits, chocolate eggs, alongside the crucifixion story of course, are not found in the Bible. Still, the modern world celebrates Easter with the same vigour as every other festival on the calendar. Christmas chocolates are now wheeled out in September and ‘Easter eggs’ are in the high street stores from mid January in the Western comercial world, as the consumer machine goes into overdrive at the festival dates watched over by Orion. The lucid giant Orion remains dominant in the skies as Saturnalia (Christmas) ends, and a new light or sun is born as we head into the New Year. The star man, Orion, stays upright and strong through the winter months up until the first rites of spring, where he starts to decline (decend) at the time we call Easter and Beltaine.

Lunar Calendars and the ‘Time of the Crossing‘

Easter relates to the moon (or moonthly calendar) also known as a ‘moveable feast’ because it does not fall on a fixed date in the Roman Catholic-inspired Gregorian or Julian calendars. Easter is never the same day each year. Roman Catholic calendars follow the ‘cycle of the sun’ with ‘irregular’ Moon days and therefore Easter time, is determined through what is called a lunisolar calendar, similar to the Hebrew calendar. In 325 AD the Council of Nicaea decided Easter would fall on the first Sunday after the ecclesiastical full moon or soonest moon after the Spring Equinox on the 21st March. Those ‘Pagan founding fathers’ of the Roman Christian church knew how to ‘use’ the moon to create a calendar that would suit their own agenda for global prominence. Saturn (or dark star), underpins the vibrational (the invisible) structure given to us by the Moon and therefore, Roman calendars are no more than a Saturn-Sun & Moon vibrational measurment of time – or illusion. Authors like David Icke have called it the ‘Saturn-Moon Matrix’. Time, as a construct, is purely based on measurements of the movement of celestial bodies, so to keep the human mind locked on the illusion of time. Beyond the illusory clock created by the sun and moon, there is no time, only unlimited infinite ‘timelessness’ (see figure).

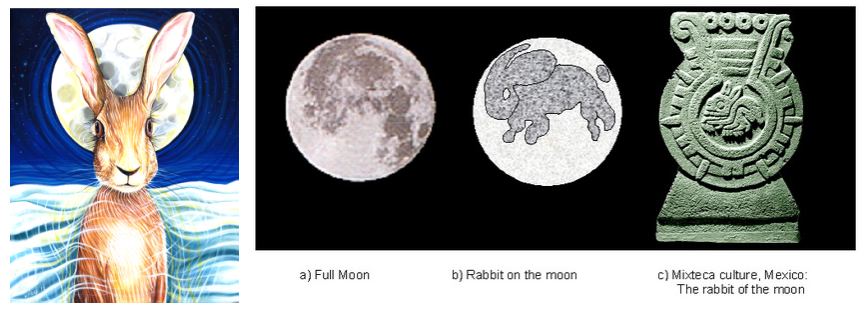

The sun and the moon are ‘markers of time’, but time as a concept was ‘originated’ by Cronos (Saturn). Both the sun and the moon ‘manage light’, creating night and day, therefore reinforcing the ‘illusion of time’. The white rabbit and his ‘pocket watch’ in Alice in Wonderland, for example, is another symbol for the moon (with Saturn) and the Goddess (Alice) in ‘wonderland’ – the illusion. In other words, Alice (the goddess archetype), is trapped by time in the Saturn-Moon matrix of twenty-four hours, twelve months, and so on. These are the numerological ‘constructs’ that reinforce the moon’s influence over ‘our time’. And how do we spend most of our waking time? Working to earn ‘Mooney’. In ancient Chinese and Japanese calendars, hours were counted through animal names, and for these cultures an ‘artificial day’ began at six o’clock in the morning when the sun rises in the middle of what they called the ‘Hour of the Hare’ (or ‘crossing’). It was the hour of the crossing, between night and day, when Orion, with Lepus the hare, can be seen to decline turning west after sunset (see figure below). At this time, Jupiter and Saturn also slowly move westward each night and Venus marks the dawn sky becoming the ‘Morning Star leading the Sun as it travels across the sky. It’s as though Orion and Lepus together, offer ‘renewal’ as the spring appears, and Easter dawns.

Passover – Easter

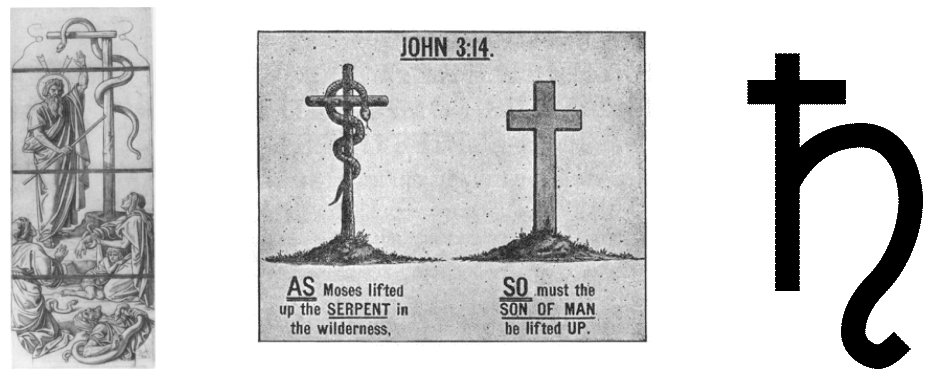

Easter is also linked to the Passover (‘Pesah’ or ‘Pesakh’ in Assyrian) through much of its symbolism, as well as through its position in the lunisolar calendar. Jewish people celebrate Passover as a commemoration of their liberation by God from slavery in Egypt thanks to Moses (the Exodus), which I understand, but I cannot help but wonder if the skies at this time are highly significant to such nar- ratives, too? The Nehustan (the brazen serpent on the cross attributed to Moses) gives us more insight into the ‘Passover-Easter’ (Saturn-Sun) connection. The serpent symbolism refers to ‘chaos calmed’ and given a ‘new order’ that can be connected to ‘Ophiuchus’ (the snake bearer) and Serpens Caput (Serpent Head) to the west, and Serpens Cauda (Serpent Tail) to the east. All of which oppose Orion’s ‘position’, as explained in my book, Orion’s Door.

In this case, the Moses or Jesus (Orion) saviour figure is both the snake, and the sun, resurrected at Easter. It is also said the ‘light of the world’ too, is ‘renewed’ at Easter (or spring time) and the numerous saviour figures, found in ancient myth, are symbols for this renewal on one level (see figures below). Interestingly, Passover (Easter) arrives through the first month called ‘Nisan’ (or Nissan) on the Hebrew/Assyrian calendar, which is the month of April in the ecclesiastical year. Nissan, of course, is the name of a automobile corporation and its symbolism seems to be another image variation of Saturn.

The Goddess Ostara (Easter)

In ancient Indo-European myths ‘Ostre’ or ‘Ostara’ was associated with the ‘light of spring’ (the light of the world) and the goddess who brings ‘new light’. You could say she made the clocks go forward, so to speak. Ostara is also linked to Easter, hares and ‘sacred eggs’ and is another version of mother nature (the awakening feminine principle) behind the sun’s light. She is also a variation of the goddess, Sophia. In other forms, she is known as Ishtar (star), Freyja and Anunitu, who on the Spring Equinox, was said to mate with the ‘solar god’ (the sun) and conceive a child that would be born nine months (or moons) later on the Winter Solstice.

The Mesopotamian (Akkadian, Assyrian and Babylonian) goddess, ‘Ishtar’ was another version of Ostara – the goddess of light, among other things. She was also the goddess of fertility, love, war, sex and power. Ishtar, like Ostara, was said to have ‘two sides’, or ‘two natures’, both creative and destructive. Ishtar is also ‘Aja’ (the eastern mountain dawn god- dess) and ‘Anatu’ (possibly Ishtar’s mother). She is also ‘Anunitu’ (the Akkadian goddess of light), ‘Agasayam’ (war goddess), ‘Irnini’ (goddess of cedar forests in the Lebanese mountains), ‘Wenet’ (Egypt), ‘Kilili’ (symbol of the desirable woman), ‘Sahirtu’ (messenger of lovers), ‘Kir-gu-lu’ (bringer of rain) and ‘Sarbanda’ (power of sovereignty). Both Ostara and Ishtar (same deity in truth) usher in the ‘time’ we call Easter.

The Ancient Hare and Rabbit Goddesses

The main animal symbol used in pagan lunar magic, nature and witchcraft is the ‘hare’. Many of the goddesses mentioned in this chapter were either said to have a hare as a companion, or could take the form of a hare. In ancient Egypt, Osiris was sacrificed to the Nile each year in the form of a hare to guarantee the annual flooding that Egyptian agriculture (and indeed their entire society) depended upon. A minor Egyptian goddess ‘Unut’, or ‘Wenet’ also had the head of a hare. The hieroglyph ‘Wn’ (Wen) itself stands for the ‘essence of life’ and often depicts a hare overflowing water. The hare is often depicted ‘greeting the dawn’ (the ‘hour of the hare’) and she sometimes serves as a messenger for the god, Thoth, (Sirius), Wenet (Lepus) and Osiris (Orion) are the three main constellations that usher in the turning points of the autumn and spring equinoxes.

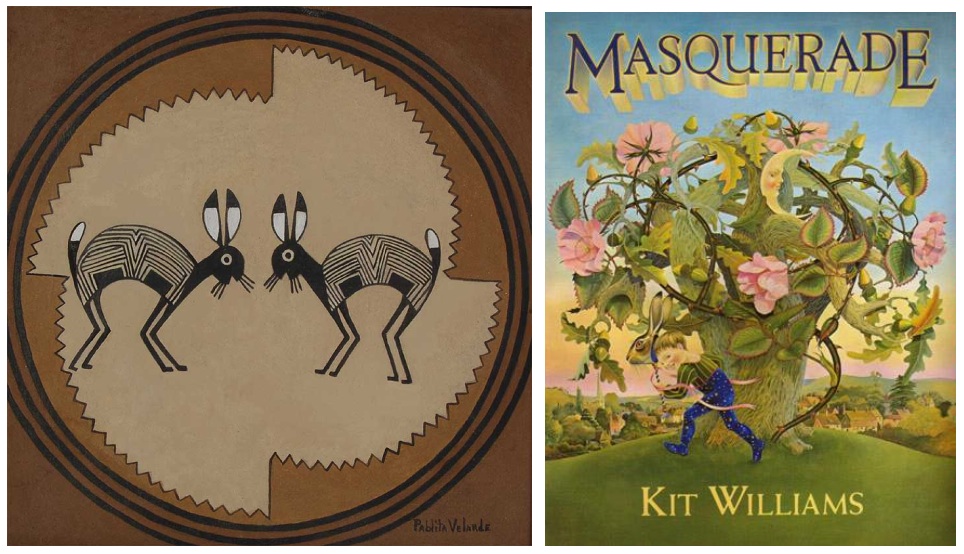

In numerology, three is considered to be feminine and the tarot card representative of the three ‘energetically’ is the Empress – Hecate – Ostara – El. Three is also the ‘Trinity’ and these are the three aspects of ‘Shin’ whose ‘three wicks’ are a symbol of the ‘holy trinity’ through the letter Shin. In many uses of numerology and ancient belief, three is an important number for ‘creating reality’ and ‘manifestation’. The symbol of the ‘three hares’ found at sacred sites from the Middle and Far East, to churches in Devon, UK are all versions of Hecate’s (Ostara’s) ‘power of manifestation’ and ‘renewal’ (below left).

The Italian Renaissance painter, Andrea Mantegna, a Knight from a ‘bloodline of painters, depicts ‘three hares’ in his masterpiece, The Agony in the Garden (1458-60) above right. The full painting shows angels bearing the Instruments of ‘the Passion’ appearing to Christ in prayer in the garden of Gethsemane. In the painting, three disciples sleep, with three hares at their feet and in the background, Judas comes with soldiers to arrest Christ. The symbolism, obviously known to Mantegna (and elite circles of his time), relates to the Trinity of the Church born out of the Passion, on one level; however, it also relates to fertility, lunar cycles and the ‘goddess of renewal’.

In the St John the Baptist Cathedral in Valletta, Malta, a Knights of Malta tomb clearly depicts Lepus (the hare) and the ‘Shin’, or possibly three belt stars of Orion (see figure below). The tomb sits alongside many other tombs littered with images of grim reapers and skeletons with axes and other ‘Orion-Saturn symbols’. As I mentioned in Orion’s Door, the Teutonic Knights of Malta, who adored John the Baptist (the headless god), understood the celestial symbolism associated with Orion and Lepus, along with the ‘passage of the sun’ and moon creating ‘time’ (Saturn).

The Goddess & the ‘White Rabbit’

Celtic myths talk of the goddess, ‘Cerridwen’, who represented the human cycles of birth, life, death and rebirth. Cerridwen was another moon goddess associated with the hare. In one legend, the hunter Ossian (Orion) was said to have wounded a hare forcing it to find sanctuary in a thicket. When Ossian wounded the hare (possibly Lepus), he found a ‘door’ in the ground that led to a vast hallway and in that ‘underground kingdom’, he met a beautiful woman sitting on a throne, bleeding from the leg. Tales like this are plentiful in the pre-Christian world and hint at metamorphosis and parallel worlds connected to different gods, planets, stars and of course the Moon Rabbit.

A Japanese myth also tells of the ‘Hare of Inaba’ and the goddess, ‘Amaterasu’, and her search for a place for their palace or ‘kingdom’. Like the white rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, Inaba suddenly appears to point the way to Amaterasu (see figures below). According to the folk tale, the white hare bites Amaterasu’s clothes and takes her to an ‘otherworldly’ location to look for a temporary palace at Nakayama Mountain and Reiseki Mountain. The ‘mountain’, the ‘Goddess’ and the ‘white hare’ are all sym- bols for the starlight, the moon, time and forces that create the collective world reality’.

Trickster Hares

Some native cultures saw the hare as a ‘trickster’ or ‘shape-shifter’ akin to the Gnostic understanding of what they called the Demiurge. The hare appears in English folklore in the saying “as mad as a March hare” and in stories of a witch who takes the form of a white hare and goes out looking for prey at night. The Br’er Rabbit stories are loosely related to the trickster element of the rabbit and hare, as mentioned earlier. Interestingly, the hare was said to be a ‘child of Pan’ and in many myths the hare was wrapped in ‘goatskin’, another Saturn connection.

Kit Williams’ Book Masquerade (1979) relays the ‘trickster element’ of the hare. The book’s objective, the hunt for a valuable treasure, became his means to this end. Masquerade features ‘fifteen’ (Saturn’s number) detailed paintings illustrating the story of a shape-shifting ‘hare’ named Jack. The boy/hare, Jack, seeks to carry a treasure from the moon (depicted as a woman) to her love object, the sun (a man). On reaching the sun, Jack finds he has lost the treasure, and the reader is left to discover the location of the ‘golden hare’. Was author Kit Williams inspired by pagan myths associated with the sun, moon and hare?

In other folklore and legends, we have mythical hares that are hybrid creatures, such as the ‘Lepus Cornutus’ and ‘Al-mi’raj’ (an Arabic mythical unicorn hare). In Bavarian folklore there are stories of the ‘wolpertinger’ (also called ‘wolperdinger’), a mythological hybrid hare allegedly inhabiting the alpine forests of Bavaria and having antlers.

The púca (Irish for spirit/ghost), pooka, or púka is another hare-like creature of Celtic folklore (see below). A púca was considered to be an omen of both good and bad fortune, or could either ‘help or hinder’ communities. These creatures were said to be ‘shape-changers’ (shape-shifters), taking the appearance of black horses, goats and hares. Images of this kind, along with the Trickster Hare, may well have been ‘connecting’ Lepus and Monoceros, the constellations adjacent to Orion, as they moved across the ecliptic.

The Primordial ‘Easter Egg’

Another symbol of Easter is the egg of course, a universal symbol for ‘birth’ and ‘new life’. The ‘primordial egg’ holds the seed from which the whole of manifes- tation was said to have ‘sprung’.

The egg is a symbolic ‘boundary of the restriction’ between ‘matter’ and other bodies making up the human being. In William Blake’s image, The Four Zoas, we are shown the four bodies of the mind, emotion, senses and imagination surrounding the egg. The cosmic egg, born from primordial Waters, in some myths, splits into two halves giving birth to Heaven and Earth (Symbolised as Adam and Satan in Blake’s image), or as the Hindu Brahmânda and the ‘two Dioscuri’ in Greco-Indian myths. In Hindu mythology, Brahma – the omniscient (the source of all-that-exists) forms out of the golden embryo and egg. According to Hindu belief, Brahma was the self-born ‘uncreated creator’, the first manifestation of The ‘One’s’ existence.

Druids saw the egg as a sacred emblem in their initiation rites, hence the egg’s importance in spring (at Easter). The procession of the goddess of agriculture, Ceres, in Rome, was preceded by an egg and it was often depicted entwined by a serpent or crowned by a crescent moon, we are back to Ophiuchus again. In the mysteries of Bacchus in ancient Greece, the egg was also a consecrated emblem that symbolised the ‘soul’ and this symbolism was portrayed in the movie Angel Heart (1989), when ‘Louis Cyphre’ (Lucifer), played by de Niro, peels an egg and eats it as a symbol of the ‘consumption of the soul’. The ‘eye and egg’ are other symbols for the ‘theft of the soul’ in occult symbolism, or the visionary limits of ‘perception’ placed on humanity by the Demiurge. All over the ancient world, from China to Babylon, the egg was also painted, and venerated as a symbol of rebirth and the soul. The ‘soul of humanity’, captured, bound or ‘eaten’ is a common theme through the use of the symbol of the egg.

Personally, I always see Easter as a period of ‘transition and renewal’, a time for ‘new ideas’ and ‘new beginnings’. The time of year can also be used by ‘darker forces’ to force changes on humanity (see the coronavirus pandemic and the lockdowns that followed leading up to Easter 2020 all across the world). Watch each Easter like a hawk, because something usually is anounced or comes to the surface at this time and around May the 1st (Beltaine).

Easter is the festival of visible new light and life emerging from darkness. The symbolism behind the moon egg, the hare and the goddess represent the interconnectedness of the moon, sun and Orion’s descent into the subterranean realms after the Spring Equinox. The star man dies symbolically to be reborn as such (see the Osiris myths). Easter is another ‘marker’ on the sun wheel as Orion makes his way towards spring, taking Lepus, the hare, with him. The goddess of Easter reigns, as the masculine falls gradually into the darkness, the void, to return with the sun on the Summer Solstice. The symbolism I have unravelled and explained as the ‘Orion-Saturn’ rituals, in my books and blogs, is simply ancient star, sun and moon worship, probably given to the ancients via ‘off-world’ elite priesthoods (sky-watchers) and ‘their gods’. We are still worshipping the planets, sun, stars (especially Orion) through our annual movement energetically (via the festivals and holidays) as we synch with the Pagan calendar.

Happy Ostara – Until next time.